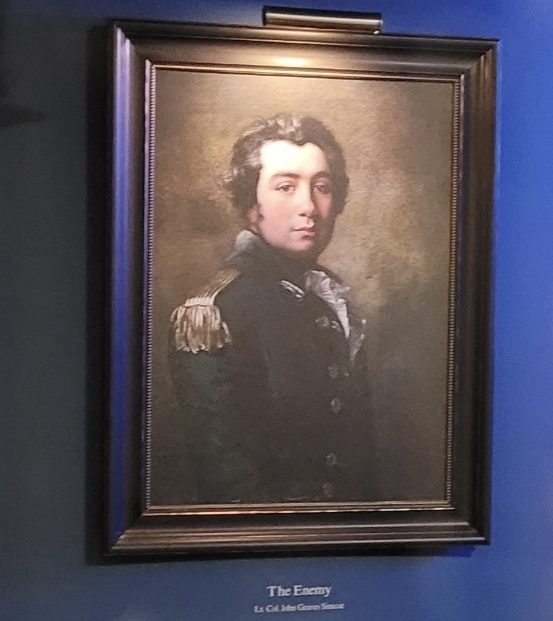

This past Halloween I attended my first Historic Ghost Tour at Raynham Hall Museum, co-led by Spiritualist Healer Samantha Lynn Difronzo and Director of Visitor Services Christopher Judge. Among other bone-chilling revelations, what they shared prompted me to reconsider my assumptions regarding Colonel John Graves Simcoe, one of the British officers who occupied the home during the American Revolution, and Sally Townsend, the younger sister of Patriot spy Robert Townsend.

Two diametrically opposed legends exist surrounding Sally. The first is that she was in love with Simcoe, owing to a now-famous valentine he gave her and reports of a sad presence lingering in the upper rooms of the house long after she died unmarried. The second is that she worked simultaneously as a Patriot spy who played a crucial role in foiling Benedict Arnold’s treason plot – although after digging deeper into the records, historians now believe it was actually Robert’s friend Liss and another enslaved woman who gathered said intelligence and relayed it to the Continental Army.

Prior to this tour I was skeptical about the Sally-Simcoe urban legend because, well, a Patriot yearning for a romantic relationship with a British officer who has been rendered especially notorious by the AMC series TURN (2014-2017) seems unlikely.

In fairness, Simcoe is actually one of very few British officers the series demonized; many others, including Major Hewlett and John André (as well as the fictional Ensign Baker,) rank among its most-loved characters. Simcoe likely made a convenient villain due to three factors:

1) His interaction with numerous members of the Culper Ring. This probably goes without saying, but geography alone made Simcoe a reality for Manhattan- and Long Island-based spies – especially Robert Townsend, whose childhood home he essentially moved into without permission!

2) His occupation of Raynham Hall and the town of Oyster Bay. It’s hard to imagine most citizens would enjoy having a small army move in, cut down their apple orchards, and craft a fort ringed with spikes on the hill! With resources already strained due to the war, it would also have proved logistically challenging for such a small community to support a sudden influx of soldiers – even if you were a Loyalist! At war’s end, only about one in every twenty Loyalists left in New York actually evacuated with the British army. The rest had presumably grown disillusioned after years of heavy military occupation ordered by their once-beloved royal government.1

3) The reputation of the Queen’s Rangers in general. Even if other regiments were more infamous for marauding, the Rangers’ rise to power as one of the Royal Army’s most effective fighting units (a turnaround Simcoe himself was responsible for) was more than enough to merit dislike from some Patriots, and after all history is written by the winners.

Before we continue, I want to acknowledge that I likely have an underlying bias of my own against Simcoe, given my unusually strong connection to Benjamin Tallmadge as a historical figure. According to Samantha, these two officers were especially polarized – she informed me and a colleague that their energies clash even now.

I immediately found this intriguing since Tallmadge got along with some of his adversaries surprisingly well – most strikingly his direct rival, British spymaster John André! The two became so friendly in the days leading up to André’s execution that Tallmadge later admitted he was somewhat scarred by his own powerlessness to interfere with it – even going so far as to defend André posthumously during a congressional hearing decades later. 2

By deduction, this suggests something markedly different about Simcoe as both a rival and colleague. Could he simply have lacked the social graces of more universally-popular officers such as André? Or did he legitimately take actions that caused friction? My interpretation is that Simcoe wasn’t objectively “evil;” instead he was a character distinct enough to provoke intense dislike from some.

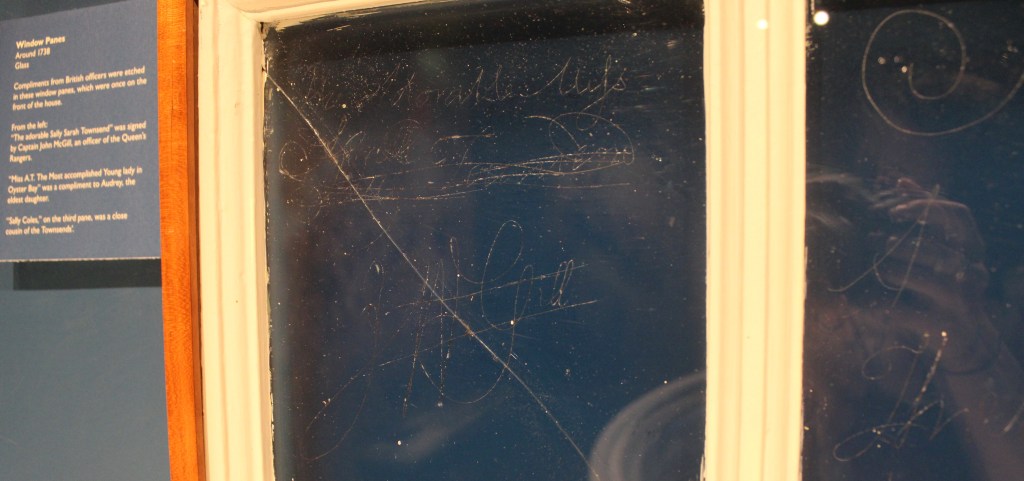

Evidently some people hated him (such as the mob who tried to kill Simcoe in New Jersey after he was injured falling off his horse,) but this Ghost Tour finally got me to consider that perhaps Sally Townsend didn’t. That doesn’t mean she reciprocated the romantic feelings he expressed in his valentine to her – we don’t have evidence aside from her keeping it – nor does her silence necessarily indicate they parted on bad terms. Their dynamic might alternatively have resembled the platonic (if sometimes uncomfortable) officer-civilian friendship TURN imagines between Hewlett and Anna Strong.

Personally, it makes my skin crawl seeing love notes scrawled in the glass at Raynham Hall from British officers to the family’s daughters, who were younger and could do nothing about their presence (except maybe spy.) But then again, I am pretty aligned with the Patriots. As I go forward uncovering truths about Simcoe and the other spirits who passed through Raynham Hall, I hope to look past the murky filters of my own bias and that of historians before me.